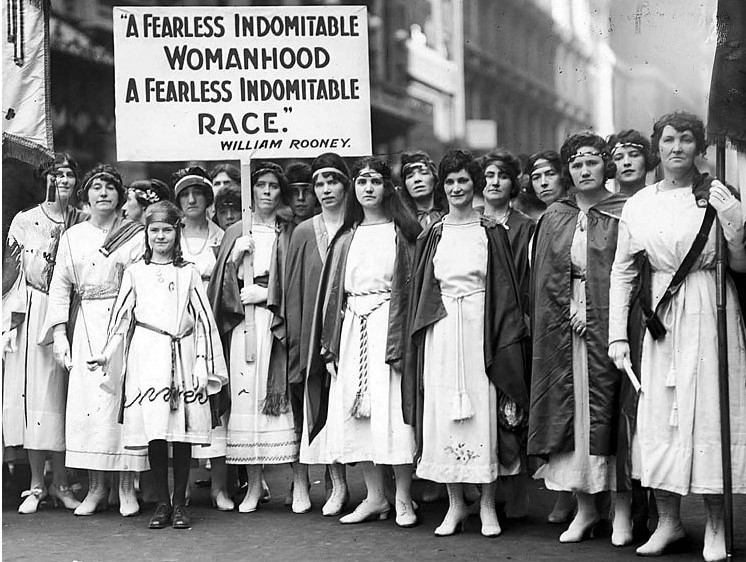

In 1968 the women’s liberation group New York Radical Women staged public demonstrations, including the Burial of Traditional Womanhood in January and the Miss America Protest in September. In June the group also published a short, typed journal titled Notes from the First Year. Alongside texts such as Anne Koedt’s “Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm” and Katie Amatniek’s “Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” was an essay by Shulamith Firestone called “Women’s Rights Movement in the u.s:’ Firestone rejected characterizations of the nineteenth-century woman activist as a “granite-faced spinster obsessed with a vote” (Firestone 1968: 1). Castigating those who spread “superficial, slanted, or downright false” information about feminist history, she identified its consequences: “To be called a feminist has become an insult, so much so that a young woman intellectual, often radical in every other area, will deny vehemently that she is a feminist, will be ashamed to identify in any way with the early women’s movement, calling it cop-out or reformist or demeaning it politically without knowing even the little that is circulated about it” (1). Firestone, like legions of activists before and after her, recommended education.

Drawing on the 1959 edition of historian Eleanor Flexner’s Century of Struggle, Firestone laid claim to the “dynamite revolutionary potential” present in the women’s movement from the beginning. He noted its connections with abolition and labor activism, and outlined its lessons for radical women of the time. Many of whom had become politically active in the New Left. She summarized: “1. Never compromise basic principles for political expediency. 2. Agitation for specific freedoms is worthless without the preliminary raising of consciousness necessary to utilize these freedoms fully. 3. Put your own interests first, then proceed to make alliances with other oppressed groups.

Demand a piece of that revolutionary pie before you put your life on the line” (Firestone 1968: 7 ). Asserting that “women’s rights were never won:’ she urged her contemporaries to continue the fight on economic, social, cultural, and legal grounds.

Firestone’s short essay not only sought to diminish the ignorance of activists of the 1960s about the heritage of US women but also recovered the experiences of earlier women as models and as cautionary tales to be applied in the present. She wrote in the informal idiom common to radical political movements of the 1960s, calling the antisuffrage groups of the early twentieth century “a female front for big money interests” (Firestone 1968: 3), noting the close ties between “the Black Struggle and the Feminine Struggle” (2), and bemoaning women’s routinized “shit jobs” (7) that fell far short of economic power. Rejecting the suppression of women’s history and the lies told by institutional authorities, Firestone’s essay led Notes from the First Year as an incendiary call to power through historical knowledge.

Firestone’s essay dramatically shows that history is not neutral or benign, and that arguments about what was significant in the past-or even about what happened-are embedded in the dynamics of the moment when the historical narrative is generated.

Appeals to the past are generated for rhetorical purposes, and the contexts of production and circulation of these appeals help to determine which aspects of the past are recovered and remembered. Whereas rhetorical scholarship is not equivalent to activist discourse, in that the audiences, purposes, and formal requirements differ markedly, it is still true that scholarly writing is rhetorical practice. Choices of subject, method, and conceptual framework are consequences of audiences, goals, and prior utterances. Firestone’s essay, with its fervent commitment to a usable past, illustrates a resonant historical connection: how we understand nineteenth-century feminism is intimately intertwined with mid-twentieth-century feminism. Furthermore, Firestone’s political lessons offer an analogical model for an evaluation of scholarship: What can we learn, what can we celebrate, and what can we do better? In this article, we argue that by attending to the past we sharpen our understanding of how we came to know and how we might know more, or better, or differently, in the future.